I have been asked this question several times since I changed jobs. Understandable, as many of my friends came to know me during my time as a bird biologist. As an expert on a niche topic in bird biology (do birds have a sense of smell?), I published a book about my research (available in print, e-book, or audiobook from your favorite online book retailer!) and gave tons of talks at academic conferences and birder group meetings. Friends would send me pictures of birds they saw and asked me to identify them, and I could always be counted upon to talk about duck penises at gatherings involving alcohol. However, the bird biology portion of my career, though admittedly long, was only one part of a winding academic path.

A dark-eyed junco - the bird I spent well over a decade studying

I started college absolutely convinced that I wanted to spend my life studying English literature. Specifically, medieval English literature. (I’m not sure why we think teenagers have the capability to decide on a life-long career.) Three years in, I suddenly decided that no, that wasn’t for me after all and changed my major to Anthropology. Somehow I got accepted into a PhD program studying biological anthropology, and spent seven years becoming an expert on a little-studied species of gibbon in Indonesia. After graduating, I took another sharp turn and got a postdoctoral position studying bird behavior and biology. I stayed there for four years, and after a long and unsuccessful search for a traditional tenure-track professor job, I landed a position as a the managing director of the BEACON Center for the Study of Evolution in Action, an NSF-funded Science and Technology Center.

Administrative jobs get a bad rep, but I really enjoyed managing the $5 million/year budget, everyday operations, and required reporting of a center with over 500 members and an exciting research portfolio. Since my work was relevant to the center’s research focus, I was able to get funding to conduct my own research, though of course the admin work took priority. Despite not having my own lab or students, I was able to cobble together several years of field seasons and collaborations with people who did have labs, and published quite a bit of interesting research.

Here are some more juncos! (I couldn’t decide which picture to use so you get both)

Funding for NSF Science and Technology Centers is limited to 10 years, and that job did eventually wind down. Lucky for me, a new round of centers had been funded, and a very interesting one - COLDEX, the Center for Oldest Ice Exploration - was in need of a managing director. I was excited to start with a brand-new center and apply all of my expertise with these kinds of centers.

But people were surprised that I was willing to move on from biology. What they didn’t seem to understand was that living on the edge of academia, with no institutional support for your research, is exhausting. I had spent years applying for small grants and begging for space in other people’s labs. I regularly got inquiries from potential graduate students who wanted to work with me, only to have to disappoint them with the news that I couldn’t take on graduate students. And, perhaps most importantly, I felt like I was kind of done with my research topic.

Sometimes I worry that I am a dilettante, not serious enough about my work to commit to any one thing for very long. I was pleasantly surprised to come across a explanation last weekend that actually makes this pattern of mine sound like a good thing.

I was in need of a new audiobook for my long runs, and I started listening to Alex Hutchinson’s new book The Explorer's Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map. I had enjoyed his best-selling book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance and thought this new one sounded good too. In the first chapter, he describes his own career path - starting as a Ph.D. in physics, then spending a year or so training in hopes of making the Olympics. When that didn’t work out, he went back to physics, only to change his mind again and get a journalism degree. Then he found his niche, reporting on the science of endurance - and the resulting book “did unexpectedly well… and it positioned me perfectly to brand myself as ‘the science of endurance guy’ and milk that role for the rest of my working life.” But, like me, he was kind of bored after exerting all that effort. And like me, he worried about the pattern he seemed to be repeating in his life - but he also knew that the “seemingly irrational” twists and turns in his career had been very fruitful and rewarding. “I was on the horns of a ubiquitous and exhaustively studied metachoice that researchers call the explore-exploit dilemma.”

You mean there’s a name for this? Indeed. Apparently in 1991, Stanford business professor James March described this tension between business models that can either innovate new things or get better at making the same things. The concept of the explore-exploit dilemma was recognized and picked up by many scientific fields including mathematics and evolutionary biology.

So: I’m not a dilettante! I’m an explorer! That’s much cooler.

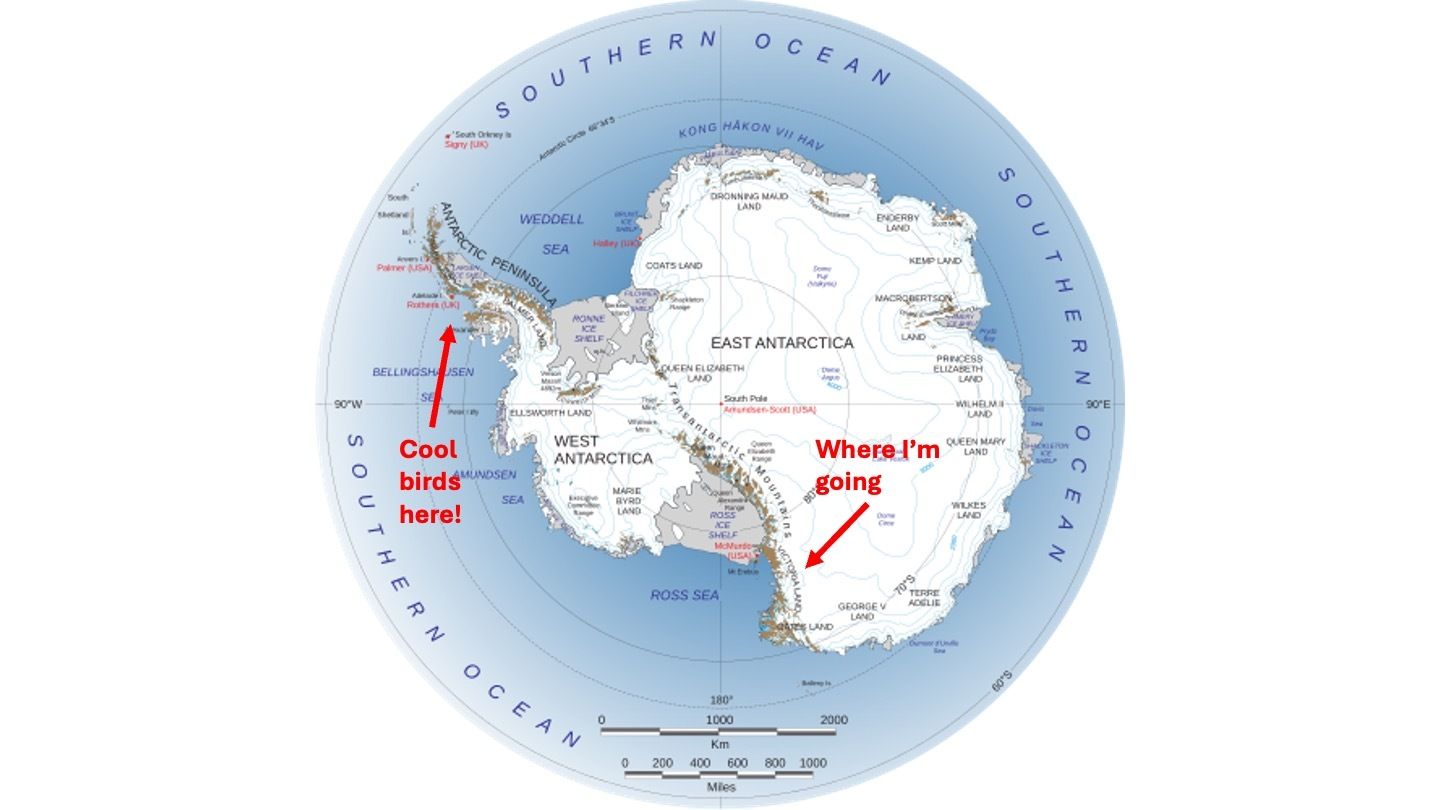

Anyway, back to the original question: what do ice cores have to do with birds? Absolutely nothing. There are a lot of really interesting birds in Antarctica, many of which I got to see when I visited a couple of years ago as a tourist. But that was on the Antarctic Peninsula, which is full of life that is highly dependent on the ocean. Where I’m going this time is just a big ice sheet. No birds, no plants, no mammals aside from the silly humans collecting ice. But that’s ok with me - I’m learning something new.

Map by Landsat Image Mosaic of Antarctica team - extracted from https://lima.usgs.gov/documents/LIMA_overview_map.pdf, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9570048. Red labels by me.

Chinstrap penguin colony on the Antarctic peninsula

What else I’m doing this week:

Reading: Besides the Alex Hutchinson book noted above, I just finished Lessons in Magic and Disaster by Charlie Jane Anders. Highly recommended to all fans of science fiction and 18th century literature! (how often do you get to put those two things in one book?!)

Eating: This insanely delicious Baked Provencal Chicken and Rice Casserole takes like 5 minutes to assemble if you don’t bother halving the cherry tomatoes and you buy pre-chopped garlic. (Sorry, life is too short for all the bureaucratic bullshit involved in fresh garlic, especially on a weeknight.)

Watching: I’m canceling our Apple TV+ subscription again because they are raising the price and we’re done watching all the series we like, except for The Studio which we are almost finished with. (I’ll resubscribe when the next season of Severance is released and then we’ll do this whole dance again.)